Tango Touch: synchronism of coupled bodies through extended touch

From the radical empiricism of William James to the discussions of autopoiesis of Maturana and Varela, we have danced around ideas of the body, isolation and shared experiences. All of these thoughts collide around the experience of tango, and the rhythm of the language of touch. So it is fitting that we examine the tango as an experiential milieu for touch as the fundamental element of communication.

The tendency of complex systems to synchronize their intrinsic temporal rhythms has applications in a wide variety of natural phenomena, from the coupling between neurons in the brain to the movements of people in society. In this research, we study the synchronism of bodies through touch, an element of synchronism that can lead to an understanding of the role of haptics in human interactions.

The tendency of complex systems to synchronize their intrinsic temporal rhythms has applications in a wide variety of natural phenomena, from the coupling between neurons in the brain to the movements of people in society. In this research, we study the synchronism of bodies through touch, an element of synchronism that can lead to an understanding of the role of haptics in human interactions.

People

Brenda McCaffrey, [email protected]

Abstract

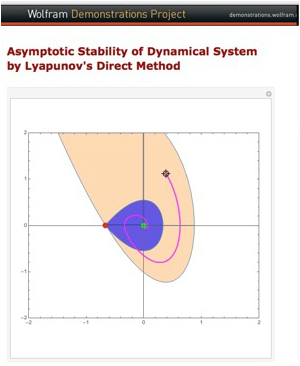

The research into the tango as an experiential milieu for touch intersects forcefully with the interest in understanding dynamical systems and using existing and possibly new analytical tools for detecting and understanding entrained engagement. Dynamical systems theory has been used extensively to shed light on many topics of scientific interest, including weather systems, electronic circuits, and human movement, to name a few. The research into ensemble interaction using experiential media shaded with insights gained from mathematical analysis of time-series data will provide significant technological challenges, and hopefully new understandings of non-verbal communication.

Videos

Motivating Questions

By the conclusion of Phase II of the Sensory Language of Tango research, a modified "embrace" was developed, XOSC devices were attached to dancers' backs, and correlation studies were completed showing that correlation between dancers could be detected through simple changes in individual movement. Phase I of the research may be found here. Details of Phase II of the research may be found here.

Proposed Research Questions for Phase III of the Sensory Language of Tango

Proposed Research Questions for Phase III of the Sensory Language of Tango

- What are the salient characteristics of synchronous versus asynchronous action in ensembles?

- All time-series dynamical systems involve feedback mechanisms. What are the feedback mechanisms in ensembles, specifically tango?

- To what degree are participants consciously aware of feedback mechanisms?

- What does synchronous or entrained behavior have to do with self-organized systems, and how can this be detected?

- Of primary interest are the bifurcations, or moments when a transition between entrained behavior and unentrained behavior emerges. How is this expressed? What analytical tools can be used to detect and analyze the transitions?

Experiential Approaches

How does one investigate somatic phenomena? The tango experiments were initially driven by a set of research questions with proposed experimental phases. Almost immediately, the experiments led to insights and understandings that were unexpected and surprising. The investigation expanded in directions to address new questions with improvised strategies. This abductive inquiry is well suited to the study of rhythm and entrainment.

"Abduction involves abstraction, but abstraction as a way of grasping, on the basis of an intuitive hunch, the possibilities of future comparison that might emerge from any given encounter or experience. This generative anticipation is developed by tracing similarities across a range of disparate activities and by producing more descriptions of these activities." (McCormack, 2013)

"Abduction involves abstraction, but abstraction as a way of grasping, on the basis of an intuitive hunch, the possibilities of future comparison that might emerge from any given encounter or experience. This generative anticipation is developed by tracing similarities across a range of disparate activities and by producing more descriptions of these activities." (McCormack, 2013)

Scientific Challenges

Challenge

The primary technical challenge is to develop methods for detecting and evaluating entrainment between bodies or ensembles using experiential and applied mathematical models based on dynamical systems thinking. Historically, these types of complex systems are only approachable through simplification and linearization techniques. We seek to use a novel combination of experiential and analytical techniques to find broad sweep understandings of self-organizing and chaotic behavior.

Methods

Experiential techniques include video, audio, motion and positional data collection on the iStage and elsewhere, using Max/MSP and MatLab, along with other adjacent programming and analytical tools. It will be important to perform video interviews of participants.

Technical

The primary technical challenge is in applying dynamical systems analytical tools in meaningful ways that do not confound the problem or lead to erroneous results. Noise in the data can mislead investigators when using conventional dynamical systems tools. An additional technical challenge will be in designing experiential explorations that do not compromise or misdirect the actions of the participants.

Overall Significance

This investigation into ensemble entrainment through tango using experiential and analytical techniques will create a research bridge between art and science. It is hoped that the experiential approach will provide new directions in thinking about synchronous behavior, while providing high order approximations for the application of analytical techniques. We wish to push the boundaries of the application of dynamical systems tools and techniques to expand the opportunities for discovery provided by experiential media.

Literature Review

Narrative Overview

Perhaps no one has looked at tango quite as closely as Erin Manning, Research Chair in Relational Art and Philosophy at Concordia.

Tango begins with a music, a rhythm, a melody.

"Tango begins with a music, a rhythm, a melody. The movements of the dance are initiated by a lead, a direction, an opening to which the follower responds. Tango is an exchange that depends on the closeness of two bodies, willing to engage with one-another. It is a pact for three minutes, a sensual encounter that guarantees nothing but a listening. And this listening must happen on both sides, for a lead is meaningless if it does not convey a message to a follower. As various tango aficionados have pointed out, the lead can never be more than an invitation, as a result of which the movement in response will remain improvised. This dialogue is rich and complex, closer to the heart, perhaps, than many exchanges between strangers and lovers." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Tango was born in the immigrant ghettos of Buenos Aires in the early 20th Century in a time when men outnumbered women by a large margin. The men were seeking the attention of the women in clubs and the tango developed as a way to create very brief and intense connection between strangers.

"Tango is one of the most alienating and sensual experiences two strangers can share. Always in reference to the exile of its displaced roots, tango is a voice where the desire to listen is burdened by the sadness of the ephemerality of the encounter with the other who will remain other. Tango is the deeply satisfying acknowledgement by the other that I have been heard, if only for a moment." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Although tango is thought of as the dance of Argentina, it spread rapidly to global acceptance with notable dance communities in the United States, Japan and Finland, among other countries. Each culture embraces the tango as an expression of tension among essentially displaced people, and these evolutions are folded back into Argentine tango. Tango engages people in a unique sensual experience. It is unique because it is a very intimate dance that puts strangers into physical contact for a few minutes in ways that few other activities can replicate. The sense of touch may be thought of as a fundamental way of communicating that occurs on a more immediate level than speech.

"The body is a sensory apparatus. Yet, the senses are difficult to grasp, difficult to condense into theories of movement. For the body senses in layers, in textures and juxtapositions that defy strict organization into a semiotic system. This is already apparent in the early work on the senses, from Aristotle to Augustine to Diderot, where we find not a convergence of theoretical understandings of the senses, but a continual re-theorizing, a re-imagining of where the senses exist in relation to the body and the mind." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Dr. Manning describes touch as uniquely personal. We may initiate touch with another person (“other”) and we are completely vulnerable to their responses, or lack of response. The very act of touching another person provides us with complex information which the mind cannot fully analyze. It goes beyond the body-mind dialectic to create a synthesis.

"Touch is the sense most likely to represent danger to the potential disruption of the mind/body dialectic, since touch refuses to be symbolized as other to the body. Nothing about touch is divine, nothing about touch is exclusionary. Touch, as a complexification of the body’s relationship to and beyond its skin, does not seem as useful as the other senses (vision, in particular) in the organization and classification of the body according to the dictates of the mind.

...Finally, tango puts the dancers into the realm of personal danger where they are completely exposed to the acceptance or rejection of another. We know what it is to hope that our touch will be accepted only to find no response, no contact. We also know what it is to attempt to convince ourselves that our touch was indeed reciprocated, that we have been received, that we have created a responsive third-body-space. We know what it is to ignore the violence of a touch which does not invent a third space but cuts across it, defiling it. This is violence, the worst violence, the violence of (the) common sense." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Philosophical considerations form a framework for thinking in vast terms about the experience of non-verbal communication through touch. In the essay, “Two Minds Can Know One Thing” (James, 1912), William James begins with an analogy about a stretchy piece of rubber. "When, for instance, a sheet of rubber is pulled at its four corners, a unit of rubber in the middle of the sheet is affected by all four of the pulls. It transmits them each, as if it pulled in four different ways at once." (James, 1912) James concludes that in a world of pure experience, a single thing can be experienced simultaneously by two minds.

In the Preface to “Autopoiesis: The Organization of the Living” (Maturana, 1980), Sir Stafford Beer describes the “iron maiden” that has resulted from millennia of organizing information into manageable silos at the expense of developing a language for synthesis. The study of touch in tango can form a framework for examining a more composite or synthesized world view. In the Introduction to “Body of Consciousness,” Professor Maturana introduces autopoiesis in terms of a unity, and noting that “…autopoiesis is necessary and sufficient to characterize the organization of living systems….” The dance environment, including the dance floor, room and music become part of the autopoietic system for the Tango.

"As soon as a unity is specified, a phenomenal domain is defined. Accordingly, if a composite unity operates as a simple unity, it operates in a phenomenal domain that it defines as a simple unity that is necessarily different from the phenomenal domain In which its components operate. …Thus, autopoiesis in the physical space characterizes living systems because it determines the distinctions that we can perform in our interactions when we specify them, but we know them only as one as we can both operate with their internal dynamics of states as composite unities and interact with them as simple unities in the environment in which we behold them." (Maturana, 1980)

Simondon addresses the problems associated with the detachment of technology from value by asserting the somatic nature of technology as emanating from a living person. "An aesthetic engagement recalls the rupture of the magical state of primitive unity, and in so doing brings the potential for reticulating it anew, enabling the emergence of a future unity." (Boucher, 2012) Ultimately, Lefebvre explores the inherent rhythms present in the world around us and encourages us to think in terms of rhythmatics.

"Rhythm appears as regulated time, governed by rational laws, but in contact with what is least rational in human being: the lived, the carnal, the body. Rational, numerical, quantitative and qualitative rhythms superimpose themselves on the multiple natural rhythms of the body (respiration, the heart, hunger and thirst, etc.), though not without changing them. ...Everywhere where there is interaction between a place, a time and an expenditure of energy, there is rhythm." (Lefebvre, 1992)

One can understand physical touch between people as an actual transfer of material, of cells, of becoming a kind of blended organism (n - 1). (Deleuze, 1988) It differs from the other senses that have a more passive engagement with others. The blended materiality is experience, not metaphor. The contact that one experiences with the other involves breathing the same air -- sharing breaths, and the transfer of cellular information. One is never the same physical being after that. Even after the momentary contact has ended, the residue of the contact remains forever, and we are transformed.

"I understand affect to be a profoundly physical concept – revealing the embodied entanglement of sensation, emotion, and thought as experience of and among bodies. From a dance studies perspective, this understanding of affect can participate in undermining any lingering dualistic notions that consciousness can somehow be unlinked from the body/bodies." (Vriend, 2015)

This leads to the concept of the rhizome as discussed in Deleuze’s introduction to A thousand plateaus (Deleuze, 1988). "[The rhizome] has neither beginning nor end, but always a middle (milieu) from which it grows and which it overspills. It constitutes linear multiplicities with n dimensions having neither subject nor object, which can be laid out on a plane of consistency, and from which the One is always subtracted (n-1)."

Derek P. McCormack delves into the somatic world in Refrains for Moving Bodies (McCormack, 2013). His discussion of rhythm and affective spaces is helpful in understanding how milieu becomes part of the experience. This discussion of the interaction between animal and human can also be applied to the human to human interaction.

"Animal refrains are just as expressive as those emerging from and between milieus that have a more human flavor. What happens in either context is that the refrain catalyzes expressive territories moving in a zone of indiscernible sensation between human and animal: the refrain marks a process of becoming animal through a process of becoming artist. So there is a relation between gestural, sonorous, and artistic refrains transversal to human and more-than-human forms of life. Moving through the material of one therefore offers the possibility of amplifying the forces and rhythms of the other." (McCormack, 2013)

Full text resources

It is worth reviewing the original recorded interview with Julie Owens (Owens, 2015), an internationally recognized tango dancer and teacher. The primary take-away from this interview is an understanding of the roles of the leader and follower, and the political consequences of assuming these roles. As I continue to reflect on the interaction of bodies through touch, I am aware of the shift that occurs during the interaction. When one analyzes the movements and action, one is creating a dichotomy that divides the action into leading and following, the leader and the follower. When the action occurs directly in response to physical touch, the dichotomy collapses and a new organism is created.

https://vimeo.com/160147496 (Owens, 2015)

Perhaps no one has looked at tango quite as closely as Erin Manning, Research Chair in Relational Art and Philosophy at Concordia.

Tango begins with a music, a rhythm, a melody.

"Tango begins with a music, a rhythm, a melody. The movements of the dance are initiated by a lead, a direction, an opening to which the follower responds. Tango is an exchange that depends on the closeness of two bodies, willing to engage with one-another. It is a pact for three minutes, a sensual encounter that guarantees nothing but a listening. And this listening must happen on both sides, for a lead is meaningless if it does not convey a message to a follower. As various tango aficionados have pointed out, the lead can never be more than an invitation, as a result of which the movement in response will remain improvised. This dialogue is rich and complex, closer to the heart, perhaps, than many exchanges between strangers and lovers." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Tango was born in the immigrant ghettos of Buenos Aires in the early 20th Century in a time when men outnumbered women by a large margin. The men were seeking the attention of the women in clubs and the tango developed as a way to create very brief and intense connection between strangers.

"Tango is one of the most alienating and sensual experiences two strangers can share. Always in reference to the exile of its displaced roots, tango is a voice where the desire to listen is burdened by the sadness of the ephemerality of the encounter with the other who will remain other. Tango is the deeply satisfying acknowledgement by the other that I have been heard, if only for a moment." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Although tango is thought of as the dance of Argentina, it spread rapidly to global acceptance with notable dance communities in the United States, Japan and Finland, among other countries. Each culture embraces the tango as an expression of tension among essentially displaced people, and these evolutions are folded back into Argentine tango. Tango engages people in a unique sensual experience. It is unique because it is a very intimate dance that puts strangers into physical contact for a few minutes in ways that few other activities can replicate. The sense of touch may be thought of as a fundamental way of communicating that occurs on a more immediate level than speech.

"The body is a sensory apparatus. Yet, the senses are difficult to grasp, difficult to condense into theories of movement. For the body senses in layers, in textures and juxtapositions that defy strict organization into a semiotic system. This is already apparent in the early work on the senses, from Aristotle to Augustine to Diderot, where we find not a convergence of theoretical understandings of the senses, but a continual re-theorizing, a re-imagining of where the senses exist in relation to the body and the mind." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Dr. Manning describes touch as uniquely personal. We may initiate touch with another person (“other”) and we are completely vulnerable to their responses, or lack of response. The very act of touching another person provides us with complex information which the mind cannot fully analyze. It goes beyond the body-mind dialectic to create a synthesis.

"Touch is the sense most likely to represent danger to the potential disruption of the mind/body dialectic, since touch refuses to be symbolized as other to the body. Nothing about touch is divine, nothing about touch is exclusionary. Touch, as a complexification of the body’s relationship to and beyond its skin, does not seem as useful as the other senses (vision, in particular) in the organization and classification of the body according to the dictates of the mind.

...Finally, tango puts the dancers into the realm of personal danger where they are completely exposed to the acceptance or rejection of another. We know what it is to hope that our touch will be accepted only to find no response, no contact. We also know what it is to attempt to convince ourselves that our touch was indeed reciprocated, that we have been received, that we have created a responsive third-body-space. We know what it is to ignore the violence of a touch which does not invent a third space but cuts across it, defiling it. This is violence, the worst violence, the violence of (the) common sense." (Manning E. , Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch, 2003)

Philosophical considerations form a framework for thinking in vast terms about the experience of non-verbal communication through touch. In the essay, “Two Minds Can Know One Thing” (James, 1912), William James begins with an analogy about a stretchy piece of rubber. "When, for instance, a sheet of rubber is pulled at its four corners, a unit of rubber in the middle of the sheet is affected by all four of the pulls. It transmits them each, as if it pulled in four different ways at once." (James, 1912) James concludes that in a world of pure experience, a single thing can be experienced simultaneously by two minds.

In the Preface to “Autopoiesis: The Organization of the Living” (Maturana, 1980), Sir Stafford Beer describes the “iron maiden” that has resulted from millennia of organizing information into manageable silos at the expense of developing a language for synthesis. The study of touch in tango can form a framework for examining a more composite or synthesized world view. In the Introduction to “Body of Consciousness,” Professor Maturana introduces autopoiesis in terms of a unity, and noting that “…autopoiesis is necessary and sufficient to characterize the organization of living systems….” The dance environment, including the dance floor, room and music become part of the autopoietic system for the Tango.

"As soon as a unity is specified, a phenomenal domain is defined. Accordingly, if a composite unity operates as a simple unity, it operates in a phenomenal domain that it defines as a simple unity that is necessarily different from the phenomenal domain In which its components operate. …Thus, autopoiesis in the physical space characterizes living systems because it determines the distinctions that we can perform in our interactions when we specify them, but we know them only as one as we can both operate with their internal dynamics of states as composite unities and interact with them as simple unities in the environment in which we behold them." (Maturana, 1980)

Simondon addresses the problems associated with the detachment of technology from value by asserting the somatic nature of technology as emanating from a living person. "An aesthetic engagement recalls the rupture of the magical state of primitive unity, and in so doing brings the potential for reticulating it anew, enabling the emergence of a future unity." (Boucher, 2012) Ultimately, Lefebvre explores the inherent rhythms present in the world around us and encourages us to think in terms of rhythmatics.

"Rhythm appears as regulated time, governed by rational laws, but in contact with what is least rational in human being: the lived, the carnal, the body. Rational, numerical, quantitative and qualitative rhythms superimpose themselves on the multiple natural rhythms of the body (respiration, the heart, hunger and thirst, etc.), though not without changing them. ...Everywhere where there is interaction between a place, a time and an expenditure of energy, there is rhythm." (Lefebvre, 1992)

One can understand physical touch between people as an actual transfer of material, of cells, of becoming a kind of blended organism (n - 1). (Deleuze, 1988) It differs from the other senses that have a more passive engagement with others. The blended materiality is experience, not metaphor. The contact that one experiences with the other involves breathing the same air -- sharing breaths, and the transfer of cellular information. One is never the same physical being after that. Even after the momentary contact has ended, the residue of the contact remains forever, and we are transformed.

"I understand affect to be a profoundly physical concept – revealing the embodied entanglement of sensation, emotion, and thought as experience of and among bodies. From a dance studies perspective, this understanding of affect can participate in undermining any lingering dualistic notions that consciousness can somehow be unlinked from the body/bodies." (Vriend, 2015)

This leads to the concept of the rhizome as discussed in Deleuze’s introduction to A thousand plateaus (Deleuze, 1988). "[The rhizome] has neither beginning nor end, but always a middle (milieu) from which it grows and which it overspills. It constitutes linear multiplicities with n dimensions having neither subject nor object, which can be laid out on a plane of consistency, and from which the One is always subtracted (n-1)."

Derek P. McCormack delves into the somatic world in Refrains for Moving Bodies (McCormack, 2013). His discussion of rhythm and affective spaces is helpful in understanding how milieu becomes part of the experience. This discussion of the interaction between animal and human can also be applied to the human to human interaction.

"Animal refrains are just as expressive as those emerging from and between milieus that have a more human flavor. What happens in either context is that the refrain catalyzes expressive territories moving in a zone of indiscernible sensation between human and animal: the refrain marks a process of becoming animal through a process of becoming artist. So there is a relation between gestural, sonorous, and artistic refrains transversal to human and more-than-human forms of life. Moving through the material of one therefore offers the possibility of amplifying the forces and rhythms of the other." (McCormack, 2013)

Full text resources

It is worth reviewing the original recorded interview with Julie Owens (Owens, 2015), an internationally recognized tango dancer and teacher. The primary take-away from this interview is an understanding of the roles of the leader and follower, and the political consequences of assuming these roles. As I continue to reflect on the interaction of bodies through touch, I am aware of the shift that occurs during the interaction. When one analyzes the movements and action, one is creating a dichotomy that divides the action into leading and following, the leader and the follower. When the action occurs directly in response to physical touch, the dichotomy collapses and a new organism is created.

https://vimeo.com/160147496 (Owens, 2015)

References

Borgialli, D. (2016, February 27). Dance Instructor. (B. McCaffrey, Interviewer)

Boucher, M.-P. H. (2012). Gilbert Simondon: Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics. Retrieved from Inflexions: http://www.inflexions.org

Brown, C. (2016, March 1). Interactive Sound Artist and Argentine Tango Dancer. (B. McCaffrey, Interviewer)

Deleuze, G. (1988). A thousand plateaus : capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Athlone.

Dreyfus, Hubert L. "Heidegger on the Connection between Nihilism, Art, Technology, and Politics." The Cambridge Companion to Heidegger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993a. 289-316. Web.

James, W. P. (1912). Essays in Radical Empiricism. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Kohn, Eduardo, and MyiLibrary. How Forests Think. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013. Print.

Lefebvre, H. (1992). Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Magnusson, Thor. "Of Epistemic Tools: Musical Instruments as Cognitive Extensions." Organised Sound 14.2 (2009a): 168-76.Music & Performing Arts Collection. Web.

Manning, E. M. (2014). Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manning, E. (2003). Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch. Retrieved from borderlands e-journal: http://www.borderlandsejournal.adelaide.edu.au/vol2no1_2003/manning_negotiating.html

Manning, E. (2007). Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manning, E. (2009). Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Maturana, H. V. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition. Boston: R. Reidel Publishing Company.

McCormack, Derek P. "Envelopment, Exposure, and the Allure of Becoming Elemental." Dialogues in Human Geography 5.1 (2015): 85-9. Web.

McCormack, Derek P., and MyiLibrary. Refrains for Moving Bodies: Experience and Experiment in Affective Spaces. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013. Web.

Owens, J. (2015, December 3). Communication in Tango. (B. McCaffrey, Interviewer)

Schiphorst, T. (2009). Body Matters: The Palpability of Invisible Computing. Leonardo , 42 (3), 225-230.

Simondon, G. (1958). On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Paris: Aubier, Editions Montaigne.

Vriend, L. D. (2015). Refrains for Moving Bodies: Experience and Experiment in Affective Spaces by Derek P. McCormack. Dance Research Journal , 47 (1), 118-121.

Additional Scientific References

Abarbanel, H. D. I., and M. B. Kennel. "Determining Embedding Dimension for Phase-Space Reconstruction using a Geometrical Construction." Physical Review A. General Physics 45.6 (1992): 3403-11. Web.

Boccaletti, S. Experimental Chaos :8th Experimental Chaos Conference, Florence, Italy, 14-17 June 2004. 742 Vol. Melville, N.Y.: American Institute of Physics, 2004. Print. AIP Conference Proceedings .

Boettiger, Carl, and Alan Hastings. "Tipping Points: From Patterns to Predictions." Nature 493.7431 (2013): 157-8. Web.

Colinet, P., A. A. Nepomnï¸ i︡ashchiÄ, and International Centre for Mechanical Sciences. Pattern Formation at Interfaces. 513 Vol. Wien; New York: Springer, 2010. Print. CISM Cources and Lectures .

Hegger, Rainer, Holger Kantz, and Thomas Schreiber. "Practical Implementation of Nonlinear Time Series Methods: The TISEAN Package." Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 9.2 (1998): 413-35. Web.

Kantz, Holger, and Thomas Schreiber. Nonlinear Time Series Analysis. [2nd]. ed. New York; Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Web.

Khoa, Truong Quang Dang, Nguyen Thi Minh Huong, and Vo Van Toi. "Detecting Epileptic Seizure from Scalp EEG using Lyapunov Spectrum." Computational and mathematical methods in medicine 2012 (2012a): 847686. MEDLINE. Web.

Krischer, K., et al. "A Hierarchy of Transitions to Mixed Mode Oscillations in an Electrochemical System." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 62.1–4 (1993): 123-33. Print.

Kulkarni, Kuldeep, and Pavan Turaga. "Reconstruction-Free Action Inference from Compressive Imagers." IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 38.4 (2016): 772-84. PubMed. Web.

Parker, Thomas S., and Leon O. Chua. Practical Numerical Algorithms for Chaotic Systems. Berlin; New York: Springer Verlag, 1989. Print.

Pecora, Louis M., et al. "Fundamentals of Synchronization in Chaotic Systems, Concepts, and Applications." Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 7.4 (1997): 520-43. Web.

Pincus, Steven M. "Approximate Entropy as a Measure of System Complexity." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88.6 (1991): 2297-301. Web.

Robins, V., et al. "Topology and Intelligent Data Analysis." Intelligent Data Analysis 8.5 (2004): 505-15. Print.

Venkataraman, Vinay. Kinematic and Dynamical Analysis Techniques for Human Movement Analysis from Portable Sensing Devices. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University, 2016. Print.

Venkataraman, Vinay, et al. "Attractor-Shape for Dynamical Analysis of Human Movement: Applications in Stroke Rehabilitation and Action Recognition".Web.

Wolf, Alan, and Tom Bessoir. "Diagnosing Chaos in the Space Circle." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 50.2 (1991): 239-58. Print.

Wolf, Alan, et al. "Determining Lyapunov Exponents from a Time Series." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 16.3 (1985): 285-317. Print.

Yair Neuman, Norbert Marwan, and Yohai Cohen. "Change in the Embedding Dimension as an Indicator of an Approaching Transition: e101014." PLoS One 9.6 (2014)Web.

Boucher, M.-P. H. (2012). Gilbert Simondon: Milieus, Techniques, Aesthetics. Retrieved from Inflexions: http://www.inflexions.org

Brown, C. (2016, March 1). Interactive Sound Artist and Argentine Tango Dancer. (B. McCaffrey, Interviewer)

Deleuze, G. (1988). A thousand plateaus : capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Athlone.

Dreyfus, Hubert L. "Heidegger on the Connection between Nihilism, Art, Technology, and Politics." The Cambridge Companion to Heidegger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993a. 289-316. Web.

James, W. P. (1912). Essays in Radical Empiricism. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Kohn, Eduardo, and MyiLibrary. How Forests Think. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013. Print.

Lefebvre, H. (1992). Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Magnusson, Thor. "Of Epistemic Tools: Musical Instruments as Cognitive Extensions." Organised Sound 14.2 (2009a): 168-76.Music & Performing Arts Collection. Web.

Manning, E. M. (2014). Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manning, E. (2003). Negotiating Influence: Argentine Tango and a Politics of Touch. Retrieved from borderlands e-journal: http://www.borderlandsejournal.adelaide.edu.au/vol2no1_2003/manning_negotiating.html

Manning, E. (2007). Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manning, E. (2009). Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Maturana, H. V. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition. Boston: R. Reidel Publishing Company.

McCormack, Derek P. "Envelopment, Exposure, and the Allure of Becoming Elemental." Dialogues in Human Geography 5.1 (2015): 85-9. Web.

McCormack, Derek P., and MyiLibrary. Refrains for Moving Bodies: Experience and Experiment in Affective Spaces. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013. Web.

Owens, J. (2015, December 3). Communication in Tango. (B. McCaffrey, Interviewer)

Schiphorst, T. (2009). Body Matters: The Palpability of Invisible Computing. Leonardo , 42 (3), 225-230.

Simondon, G. (1958). On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Paris: Aubier, Editions Montaigne.

Vriend, L. D. (2015). Refrains for Moving Bodies: Experience and Experiment in Affective Spaces by Derek P. McCormack. Dance Research Journal , 47 (1), 118-121.

Additional Scientific References

Abarbanel, H. D. I., and M. B. Kennel. "Determining Embedding Dimension for Phase-Space Reconstruction using a Geometrical Construction." Physical Review A. General Physics 45.6 (1992): 3403-11. Web.

Boccaletti, S. Experimental Chaos :8th Experimental Chaos Conference, Florence, Italy, 14-17 June 2004. 742 Vol. Melville, N.Y.: American Institute of Physics, 2004. Print. AIP Conference Proceedings .

Boettiger, Carl, and Alan Hastings. "Tipping Points: From Patterns to Predictions." Nature 493.7431 (2013): 157-8. Web.

Colinet, P., A. A. Nepomnï¸ i︡ashchiÄ, and International Centre for Mechanical Sciences. Pattern Formation at Interfaces. 513 Vol. Wien; New York: Springer, 2010. Print. CISM Cources and Lectures .

Hegger, Rainer, Holger Kantz, and Thomas Schreiber. "Practical Implementation of Nonlinear Time Series Methods: The TISEAN Package." Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 9.2 (1998): 413-35. Web.

Kantz, Holger, and Thomas Schreiber. Nonlinear Time Series Analysis. [2nd]. ed. New York; Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Web.

Khoa, Truong Quang Dang, Nguyen Thi Minh Huong, and Vo Van Toi. "Detecting Epileptic Seizure from Scalp EEG using Lyapunov Spectrum." Computational and mathematical methods in medicine 2012 (2012a): 847686. MEDLINE. Web.

Krischer, K., et al. "A Hierarchy of Transitions to Mixed Mode Oscillations in an Electrochemical System." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 62.1–4 (1993): 123-33. Print.

Kulkarni, Kuldeep, and Pavan Turaga. "Reconstruction-Free Action Inference from Compressive Imagers." IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 38.4 (2016): 772-84. PubMed. Web.

Parker, Thomas S., and Leon O. Chua. Practical Numerical Algorithms for Chaotic Systems. Berlin; New York: Springer Verlag, 1989. Print.

Pecora, Louis M., et al. "Fundamentals of Synchronization in Chaotic Systems, Concepts, and Applications." Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 7.4 (1997): 520-43. Web.

Pincus, Steven M. "Approximate Entropy as a Measure of System Complexity." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88.6 (1991): 2297-301. Web.

Robins, V., et al. "Topology and Intelligent Data Analysis." Intelligent Data Analysis 8.5 (2004): 505-15. Print.

Venkataraman, Vinay. Kinematic and Dynamical Analysis Techniques for Human Movement Analysis from Portable Sensing Devices. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University, 2016. Print.

Venkataraman, Vinay, et al. "Attractor-Shape for Dynamical Analysis of Human Movement: Applications in Stroke Rehabilitation and Action Recognition".Web.

Wolf, Alan, and Tom Bessoir. "Diagnosing Chaos in the Space Circle." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 50.2 (1991): 239-58. Print.

Wolf, Alan, et al. "Determining Lyapunov Exponents from a Time Series." Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 16.3 (1985): 285-317. Print.

Yair Neuman, Norbert Marwan, and Yohai Cohen. "Change in the Embedding Dimension as an Indicator of an Approaching Transition: e101014." PLoS One 9.6 (2014)Web.